BY JOHN HANHARDT GUGGENHEIM MUSEUM

The Worlds of Nam June Paik is an appreciation of and reflection on the life and art of Nam June Paik. Paik's journey as an artist has been truly global, and his impact on the art of video and television has been profound.To foreground the creative process that is distinctive to Paik's artwork, it is necessary to sort through his mercurial movements, from Asia through Europe to the United States, and examine his shifting interests and the ways that individual artworks changed accordingly. It is my argument that Paik's prolific and complex career can be read as a process grounded in his early interests in composition and performance. These would strongly shape his ideas for mediabased art at a time when the electronic moving image and media technologies were increasingly present in our daily lives. In turn, Paik's work would have a profound and sustained impact on the media culture of the late twentieth century; his remarkable career witnessed and influenced the redefinition of broadcast television and transformation of video into an artist's medium.

In 1982, my longtime fascination with Paik's work resulted in a retrospective exhibition that I organized for the Whitney Museum of American Art in NewYork.1 Over the ensuing years, his success and renown have grown steadily.The wide presence of the media arts in contemporary culture is in no small measure due to the power of Paik's art and ideas.Through television projects, installations, performances, collaborations, development of new artists' tools, writing, and teaching, he has contributed to the creation of a media culture that has expanded the definitions and languages of art making. Paik's life in art grew out of the politics and anti-art movements of the 1950s, 1960s, and 1970s. During this time of societal and cultural change, he pursued a determined quest to combine the expressive capacity and conceptual power of performance with the new technological possibilities associated with the moving image. I will argue that Paik realized the ambition of the cinematic imaginary in avant-garde and independent film by treating film and video as flexible and dynamic multitextual art forms. Using television, as well as the modalities of singlechannel videotape and sculptural/installation formats, he imbued the electronic moving image with new meanings. Paik's investigations into video and television and his key role in transforming the electronic moving image into an artist's medium are part of the history of the media arts.

As we look back at the twentieth century, the concept of the moving image, as it has been employed to express representational and abstract imagery through recorded and virtual technologies, constitutes a powerful discourse maintained across different media.The concept of the moving, temporal image is a key modality through which artists have articulated new strategies and forms of image making; to understand them, we need to fashion historiographic models and theoretical interpretations that locate the moving image as central in our visual culture.

Paik's latest creative deployment of new media is through laser technology. He has called his most recent installation a "post-video project," which continues the articulation of the kinetic image through the use of laser energy projected onto scrims, cascading water, and smoke-filled sculptures. At the beginning of the twenty-first century, Paik's work shows us that the cinema and video are fusing with electronic and digital media into new image technologies and forms of expression. The end of video and television as we know them signals a transformation of our visual culture.

The first chapter of this catalogue, "The Seoul of Fluxus,"3 is a consideration of Paik's position as a Korean-born artist whose interest in art began with composition and performance. "The Cinematic Avant-Garde," a survey of independent film practices in the 1960s and 1970s, is offered as a backdrop to his engagement with various artistic milieus in NewYork and his preliminary explorations of the electronic moving image, through video, in the mid-1960s. Performance and film are integrally linked to Paik's transformation of the institutional context of television and video. "TheTriumph of Nam June Paik" documents and reflects on his heroic effort to support and articulate the expressive and compositional capacities of the electronic moving image. Paik put the video image into a vast array of formal configurations, and thus added an entirely new dimension to the form of sculpture and the parameters of installation art. He transformed the very instrumentality of the video medium through a process that expressed his deep insights into electronic technology and his understanding of how to reconceive television, to "turn it inside out" and render something entirely new. Paik's imagery has not been predetermined or limited by the technologies of video or the system of television. Rather, he altered the materiality and composition of the electronic image and its placement within a space and on television and, in the process, defined a new form of creative expression. Paik's understanding of the power of the moving image began as an intuitive perception of an emerging technology, which he seized upon and transformed. In addition to collaborating with a number of technicians such as Shuya Abe, Norman Ballard, and Horst Bauman to make new tools to rework the electronic image, Paik also incorporated sophisticated computer and digital technologies into his art to continue to refashion its content, visual vocabulary, and plastic forms.

This catalogue offers a set of exploratory observations. By clustering Paik's seminal artworks around key concepts and issues that define Paik's career and achievements, I hope to suggest the depth and complexity of his aesthetic project as he has sustained it.4 In addition, I have placed selections of Paik's writings throughout the catalogue to help illustrate these observations. The design of the catalogue, by J. Abbott Miller, offers a fresh view of Paik's art and career, much as the design of the exhibition within Frank Lloyd Wright's Modernist container sets new terms for looking at and engaging in the full range of Paik's art.Two site-specific laser-projection pieces dramatically transform the Guggenheim's rotunda: one laser projects a constantly moving display of shapes and forms onto the oculus of the skylight, while a second laser moves through a cascade of water falling from the top ramp to the rotunda floor, creating a dynamic visual display through the drops of falling water. These arresting laser installations can be viewed from multiple perspectives as the spectator walks along the ramp.The projections give expression to the dynamic dialogue between art and technology that is at the heart of Paik's contribution to art and culture.

On the rotunda floor, the artist has arranged one hundred television sets and monitors to distribute a pulsing display of his video imagery on multiple channels. Complementing these changing images are large screens installed on the sides of the rotunda, which visually link the monitors' glowing images on the ground floor to the laser projections on the oculus.

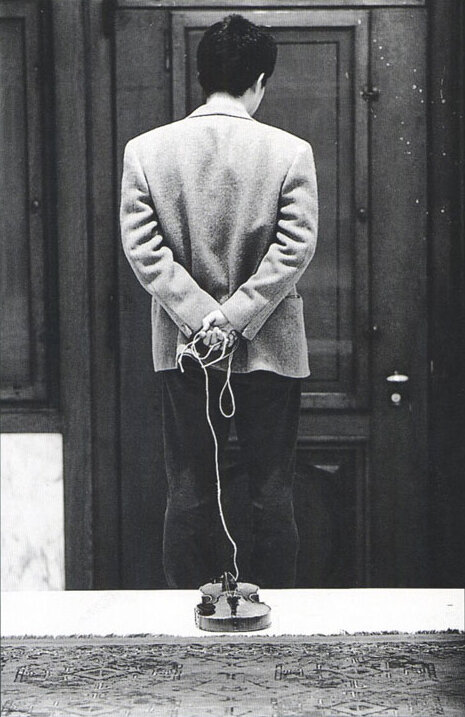

Along the ramps of the rotunda are Paik's seminal video installations including the large-scale pieces TV Garden (1974), Moon Is the Oldest TV (1965), and Video Fish (1975), which have been reconfigured by Paik to suit the unique exhibition spaces they occupy. Smaller-scale video sculptures are also installed on the ramps, including TV Chair (1968), Real Fish/Live Fish (1982), Video Buddha (1976), Swiss Clock (1988), Candle TV (1975), TV Crown (1965), and selections from Family of Robot (1986). One tower gallery will highlig tpieces from the 1950s and 1960s, which have been rediscovered and restored; early interactive video pieces including Magnet TV (1965), Participation TV (1963), and Footswitch TV (1988), accompanied by videotape and photographic documentation of original installations of this work; the Paik-Abe Video Synthesizer (1969) and documentation of video productions made with this early image processor; Fluxus objects, scores, posters, and videotape documentation of Fluxus performances that highlight this important aspect of Paik's career; and a tribute to Charlotte Moorman with her TV Cello (1971), as well as photographic and videotape documentation of her legendary performances.

Adjacent to this gallery is a single-channel screening room featuring Paik's videotapes and key collaborative works for global broadcast television, including the recently restored 9/23/69 Experiment with DavidAtwood (1969), Global Groove (1973), Good Morning, Mr. Orwell (1984), and Living with the Living Theatre (1989). In preparation for the exhibition, Stephen Vitiello of Electronic Arts Intermix was given access to the artist's personal video archive. In collaboration with Vidipax, Vitiello was able to restore a number of video and audiotapes which, until this exhibition, had been lost to public awareness. The High Gallery will feature Paik's latest laser sculptures developed in collaboration with Norman Ballard. Each of the three sculptures features a distinctive deployment of laser to evoke virtual spaces of moving light.

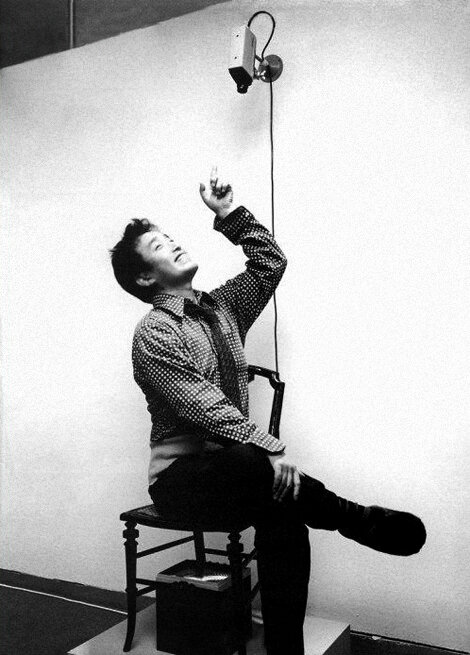

As the frontispiece for this introduction, I have chosen to reproduce a work from 1973 called A New Design for TV Chair. In it, Paik appropriated an image from a 1940s popular-science magazine that depicts the home viewer of the future watching television. Television had already become a monopolistic industry that was a conduit for advertising, a "communication" industry that operated on a one-way street of information. But in A New Design for TV Chair, Paik posited his own questions to project an alternative future for television:

DO YOU KNOW…?

How soonTV-chair will be available in most museums? How soon artists will have their ownTV channels? How soon wall-to-wal lTV for video art will be installed in most homes?

Paik envisioned a different television, a "global groove" of artists' expressions seen as part of an "electronic superhighway" that would be open and free to everyone.The multiple forms of video that Paik developed can be interpreted as an expression of an open medium able to flourish and grow through the imagination and participation of communities and individuals from around the world. Paik, along with many artists working as individuals and within collectives through the 1960s 14 and 1970s to create work for television as well as for alternative spaces, challenged the idea of television as a medium and domain exclusively controlled by a monopoly of broadcasters.

This introduction concludes with a photograph documenting Paik's Robot K-456 (1964) in an "accident" staged in front of the Whitney Museum of American Art in 1982. Paik removed his remote-controlled robot from his retrospective exhibition at the Whitney and guided it up the sidewalk along Madison Avenue. As the robot crossed the avenue, it was struck by a car and fell to the ground. Paik declared this to represent a "catastrophe of technology in the twentieth century," stating that the lesson to be gained from these tentative technological steps is that "we are learning to cope with it." Paik's staged event drew attention to the fragility of humankind and of technology itself.Twenty years after his first experiments with the television set, this street performance was made for television: after the performance, he was interviewed by television news reports; Paik took this playful moment as an opportunity to recall the need to understand technology and make sure that it does not control us. Paik's staged event with his manmade robot was a humanist expression of a technology that subverted the dominant postinstitutions. Paik, who remade the television into an artist's instrument, reminded us that we must recall the avant-garde movements of the 1960s and learn from their conceptual foundation, which expressed. the need to create alternative forms of expression out of the very technologies that impact our lives. Robot K-456 is a statement of liberation, demonstrating that the potential for innovation and new possibilities must not be lost, but must be continually reimagined and remade by the artist.

It is my wish that The Worlds of Nam June Paik will offer a new look at Paik's career and inspire a new generation of artists to recognize his relevance to late-twentieth-century art and his impact on the future of an expanding media culture.5 His everchanging images offer themselves as the fleeting memories of history and as an empowering example of the struggle to proclaim the liberating and renewing possibilities of the future.

Video art imitates nature, not in its appearance or mass, but in its intimate "time-structure" . . . which is the process of AGING (a certain kind of irreversibility). Norbert Wiener, in his design of the Radar system (a micro two-way enveloping-time analysis), did the most profound thinking about Newtonian Time (reversible) and BergsonianTime (irreversible). Edmund Husserl, in his lecture on "The Phenomenology of Inner Time-consciousness" (1928), quotes St. Augustine (the best aesthetician of music in the Medieval age) who said "What is TIME?? If no one asks me, I know ... if some one asks me, 'I know not.' "This paradox in a twentieth-century modulation connects us to the Sartrian paradox "I am always not what I am and I am always what I am not."6 -Paik, 1976

GALLERY

CARL SOLWAY

LAWSUITS

CONTACT

The Korean site has been closed.

All inquiries to be directed here.